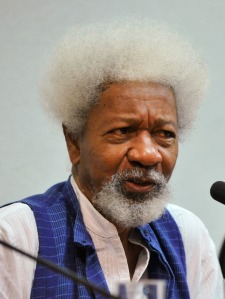

The first Sub-Saharan African to win the Nobel Prize for Literature, in 1986, Professor Wole Soyinka (Nigeria, 1934) has presided over a great body of literature for some decades. A Dance of Forests, one of his most influential plays, was presented at the Nigerian Independence Day celebrations in 1960 before being staged around the world. His autobiography Ake: The Early Years of Childhood won the prestigious Anisfield-Wolf Book Award in 1983. For a visitor of such great stature, an hour was never going to be long enough to cover the breadth of questions posed by the admiring throng of DPhil students, academics and older members of the public at the inaugural Ertegun Director’s Seminar.

In what can be the challenging time immediately after lunch, firm attention was held as Professor Elleke Boehmer interviewed Soyinka for a brief twenty minutes, before opening up to questions from the crowded floor. The conversation was a carefully crafted fabric of his views on the current state of African literature (from a pan-African perspective), international politics, and the writerly process, sprinkled with relevant personal anecdotes from a life that he casually described as being one in which he has ‘done many things.’ As the weaver, however, he decided exactly what it was he was going to speak about, often taking the questions as a departure point as opposed to something that needed to be answered directly.

He opened with a criticism of the leftist radical thought that ‘all literature is ideological’, which he said stymied a lot of early post-colonial African literature. He likened it to the millipede which stopped to count its feet and never walked again, stating that there were a number of talented writers who were crippled by their sense of ideological duty.

Soyinka felt that the current generation of African writers is freed from ideological spasms and as such is ‘varied and liberated.’ Leading the audience to imagine the kind of conversations that he has with fellow male writers from his generation, he reserved his greatest praise for contemporary African female writers, joking that as a ‘male chauvinist’ he had told his male peers, ‘Don’t let these young women catch up with us.’ The ripples of laughter continued throughout the afternoon as he peppered his talk with an easy humour.

He spoke of the liberation of women writers in general and the ways in which they were able to produce important work even whilst living in conditions where they were barely being treated as human beings. He did not refer to any of these African women writers by name, but he did mention Azar Nafisi’s Reading Lolita in Tehran. Noting that ‘imagination takes refuge from the unacceptable sometimes’ he described his own experience in solitary confinement writing nasty curses in Spanish about his jailors inside empty toilet rolls that he later turned into mobiles. Soyinka’s opposition to the Nigerian Civil War led to his spending 22 months in solitary confinement. Aware of the risk he was taking by writing, he chose to express himself in a language that he said he hoped by the time those who were detaining him were able to translate, he would have been freed; else he would have to, as he understated, face the consequences. It was this creative force, which he said ‘a true writer will find on her own’, that he consistently referred to. Even so, he avoided becoming didactic during the conversation as he guided it with a lightness of touch, joking about issues that could otherwise cause despair. He was harshest on critics who he said ‘are insolent to legislate for writers and are anti-creative’, though he tempered this later in the conversation: ‘the beauty of all these questions is that it does not stop creative expression and it keeps critics happy.’

Providing a potted history of the politics of language that followed independence across Africa, he expounded his own view (and that of many other African writers at the time) that there should have been an African lingua franca. He explained that indeed in the 1970s Kiswahili, being the most neutral and flexible, was decided upon. However, even though it would have been easier, he admitted that despite certain efforts it did not play out in reality. The relationship that different people in different African countries had to indigenous and colonial languages was too complex to easily unify.

Language being a ‘vector of culture’, and given the current climate in the UK, it was perhaps unsurprising that the conversation turned to Brexit and the rise of ultra-nationalism. Here he spoke from the personal, noting that it was neither ‘new’ or ‘surprising’ as ‘we were there when Enoch Powell’ spoke, referring to the infamous ‘Rivers of Blood’ anti-immigration speech. He reminded the audience that this took place after Britain had imported Jamaicans as labourers to help rebuild the country after the war.

While noting that it is a time when people are saying that their way of life ‘is being threatened’, he was alarmed by politicians in trouble instigating situations that ‘propelled people in lunatic directions that make them lose their humanity.’ Yet it is in the arts that hope resides as he remarked that ‘literature has always been transcultural’. He encouraged the audience to swim against the tide of obstacles by ‘just saying no and forging alliances.’

The way in which Soyinka responded during the conversation was exemplified in his answer to a question from the floor about how useful literature is as a category following the 2016 Nobel Prize for Literature being awarded to Bob Dylan. He replied that ‘I decided not to get involved in that argument, I have not had time to digest this event properly…’ before going on to joke that given the number of songs he has written for his plays he should be nominated for a Grammy. From the warm laughter and rapturous applause, it was evident that although for some it might have not been the conversation they had hoped for, it had been an illuminating hour all the same.

JC Niala

We are on Twitter @Oxford_Culture, and on Facebook