There is a something brooding about that face, probably the artist’s own. In The Portrait of a Youth (c. 1500-1) the application of the chalk on the paper is delicate, feathery, with only a few bold lines used to describe his face – handsome, innocent, with a slightly guarded gaze. This drawing, which greets visitors at the Ashmolean’s new exhibition, Raphael: The Drawings – reveals that already in his youth Raphael’s drawings were as sensational as his painted works.

Black chalk on white heightening (now largely lost), 38 x 26.1 cm

© Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

Even in his own lifetime, Raphael’s serene, mathematically pure compositions were studied as the model of classical perfection. He was so admired that when he died on Good Friday, at the age of 37, his death was mourned as if it were a second passion. Giorgio Vasari captured this general sentiment in The Lives of the Artists (1568): ‘As he embellished the world with his talents, so […] does his soul adorn Heaven by its presence’.

To contemporary minds, Raphael’s paintings can appear staid and remote when compared to the works of the Michelangelo and Da Vinci. The formality betrays coldness, his idealisation a want of human emotion. The Ashmolean’s exhibition aims to shatter this image of an effortless genius, and to completely transform our understanding of the artist. By bringing together 120 of Raphael’s most accomplished drawings, the display brings us into direct contact not only with the products of his hand and eye, but also those of his mind as he refines his ideas, techniques, and modes of expression.

Walking into the display, we first encounter his earliest drawings, produced as he began to establish himself in Florence. In them he shows a preference for clear, exact drawing, usually with a pen and ink. They are often quick, experimental works, roughly conveying the figure in a few scratchy lines. His drawings for The Madonna of the Meadows (c. 1505-1506) show Mary twisting her body toward the Christ-child, restraining him, while he eagerly tries to escape her grasp. The idea here is further developed in a chalk drawing, The Virgin with the Pomegranate (c. 1504). Mary gazes down despondently at a pomegranate in her right-hand, a symbol of the resurrection; the child grabs the fruit, apparently intrigued.

Black chalk with compass indetantion for the halo, 41.2 x 29.4 cm

© Albertina Museum, Vienna

Raphael’s mind appears to have been animated by contrast. The juxtaposition of understanding and innocence in his Madonnas gives way later in his career to depictions of male violence and female grace. The most striking drawings on display are the studies for The Massacre of the Innocents (c. 1509-10), a composition never realised as a painting. Here the restrained formality of Raphael’s composition serves to heighten the impact of the violence. One woman is turning away, an audible scream of despair on her face, as a man bears down upon her and her child with a sword. At the centre of it all, another woman is looking the viewers straight in the eye as she runs towards them – her mouth open, but speechless . The men are all mass and muscle, their eyes black pits, devoid of empathy as they carry out their bloody task.

Pen and brown ink over red chalk and geometrical indications in stylus, selectively pricked for transfer, 23.2 x

37.7 cm

© Trustees of the British Museum

Moving through the galleries, we watch as Raphael begins to experiment with new ideas and media for drawing. The most striking development from around the period in which he moved to Rome – where he would produce his most sublime work – is in his use of chalk. This material drew him to a less precise, though more expressive style, lending itself to a more tonal view of humanity. A belief in the fundamental goodness of humanity is recognisable in his sketches for The Fire in the Borgo (c. 1513-1514). As fire ravages the city, the people of Rome band together to save their own. In one sketch, a muscular young man carries an old one away from the flames; that dark menacing bulk used in service of charity as well as destruction.

Red chalk, 30 x 17.3 cm

© Albertina Museum, Vienna

The final gallery houses the drawings produced in the years before his untimely death, some of the most productive of his career. There is a tenderness, honesty, and passion in these images, which never quite translated into his painting. The Three Graces (c. 1517-1518) is a conceptually brilliant study of the nude from three different angles. Bending forwards to peer into the water are not figures of idealised perfection: they have a certain human sensuality about them. Raphael’s lust for life is apparent at every stroke.

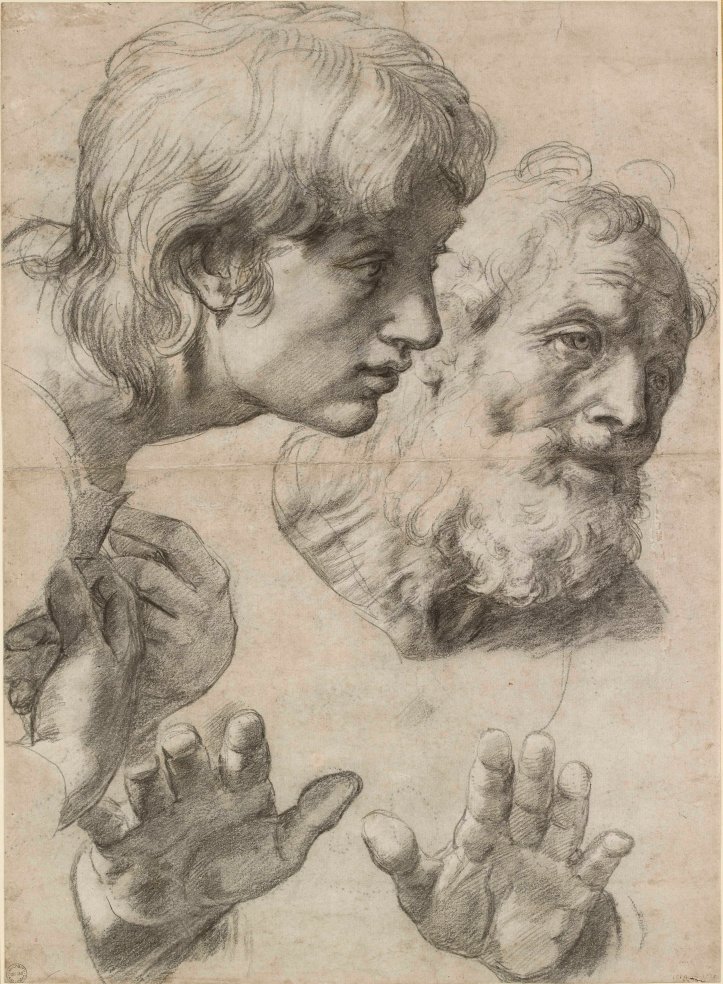

The final work in the show, The Heads and Hands of Two Apostles (c. 1519-1520), balances chiaroscuro to capture every crease on the face, every muscle in the hands, ultimately to draw out the antithesis between young and old. It has been called the most beautiful drawing in the world, more beautiful than the finished painting. These are not just preparatory sketches, but fully realised works of art. Only when we see them in their own right can we recognize the artist in all his beauty and boldness.

Black chalk with over-pounced underdrawing with some white heightening, 49.9 x 36.4 cm

© Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

Charlotte Taylor

‘Raphael: The Drawings’ runs at the Ashmolean, until 3rd September. To read more about the exhibition and to buy tickets, please visit the museum website.

[…] 16th June 2017, Oxford Culture Review […]